We’ve been prompted to write this post by the recent controversy around the 40th anniversary of Band Aid – with the re-release of ‘Do They Know It’s Christmas’ having provoked criticism from Africans both on the continent and in the diaspora.

In his Guardian article (https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2024/dec/03/criticism-bob-geldof-band-aid-charity-single-africa-caused-storm-fuse-odg) Fuse ODG complains that the single ‘inadvertently contributed to a broader identity crisis for Africans, portraying the entire continent as one monolithic, war-torn, starving place’ (see this article in The Conversation for more context and a reply from Bob Geldof).

Fuse talks instead about how Africa ‘has become a hub for groundbreaking advancements’, and this prompted us (as we do whenever we hear any interesting world news) to dive into the BLDS Legacy Collection. We were looking for other narratives challenging those of inherent Global North technical superiority and inevitable Global South dependency, including ideas from the 1970s which posed a potentially more radical critique/solution than those suggested by Fuse (note that Fuse talks about his own entrepreneurship and helping others to become entrepreneurial. Social entrepreneurship has become the leitmotif for social change today, compared to solidarity and mass politics earlier. The trouble with the social entrepreneurship model is that it does not alter the basic political economy, and so struggles to create the conditions whereby everyone can contribute in different ways to the design and provision of goods and services).

The collection is full of this material of course, but one item that caught our eye in particular was Casting New Molds: First Steps toward Worker Control in a Mozambique Steel Factory.

This is a fascinating publication from the Institute for Food and Development Policy, featuring an interview with systems analyst Peter Sketchley from Nottingham, who was a solidarity worker in Mozambique from 1977 to 1979 (On one level, it is easy to misconstrue this in the same mold as Band Aid – white saviour. But reading the account it is clear that Sketchley sees himself as having gone in solidarity and to work with Africans, not sell them stuff or give them aid). The interview takes place just after his return, with his thoughts and insights about the experience still fresh.

Mozambique became independent from Portugal in 1975, and Sketchley depicts a country both exploited and then abandoned by its colonisers. His work centres on the CIFEL steel factory based in Mozambique’s capital city Maputo, and efforts to boost production and institute a radical new model of workers control (consistent with the socialist aspirations of newly independent Mozambique). Workers who have never been properly trained (or in many cases educated) are both struggling to keep the factory going in the absence of Portuguese technicians and managers, and to throw off the colonial mentality of inferiority that has been inflicted deliberately upon them for generations.

What’s great about his account is first its honest refusal to paint a black and white picture of the project – while mistakes are made and massive problems remain, Sketchley still remains optimistic that while ‘Mozambique is not a workers’ paradise, not a model for all third world societies … its experience shows some very positive trends’ (p. 55).

The second really valuable aspect is how empirical and practical the account is. He gives examples of how the new ploughshare production (colonial production having previously been for ‘luxury’ products for the colonisers, whereas the plans now were to use the steel for products useful to rural Mozambique) was threatened by the use of wrong types of sand in the process (which the former Portuguese managers had never instructed their workers in) and how a lack of foreign exchange meant thermometers could not be fixed and furnacemen were left gauging temperatures by eye (actually this does sound a bit like Sussex library).

It’s useful to take this bottom up account and relate it to some other materials in the collection which are coming from the opposite direction. At the same time that Sketchley is in Mozambique, the UN Conference on Science and Technology for Development (UNCSTD) took place in Vienna in August 1979. This had emerged from the debates over the New International Economic Order (NIEO) and sought as part of this to instigate a New International Scientific and Technological Order (NISTO), with Guy Gresford, Deputy Secretary-General to the Conference, stating that,

“The emphasis has shifted from the concept of developed countries offering useful morsels of technological know-how to international cooperation aimed at strengthening the scientific and technological infrastructure and capabilities of the developing countries themselves.” (Gresford, 1979)

This was thus an international level attempt to address the same problems that were manifesting for Sketchley in a lack of trained technicians, raw materials, equipment and foreign currency.

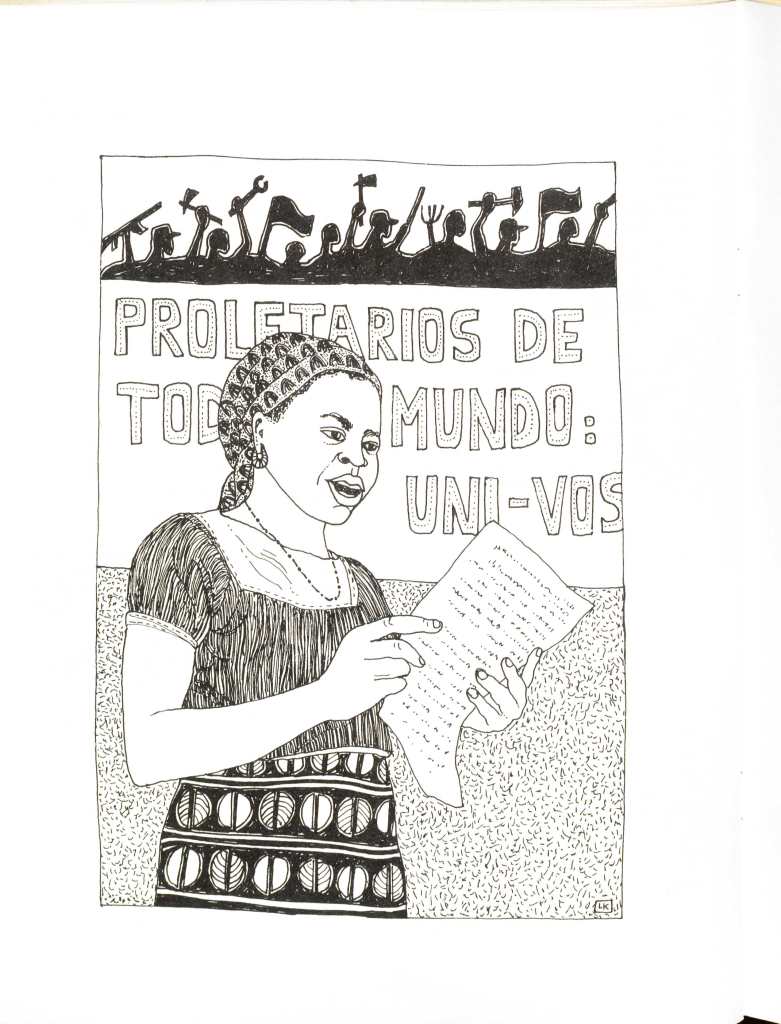

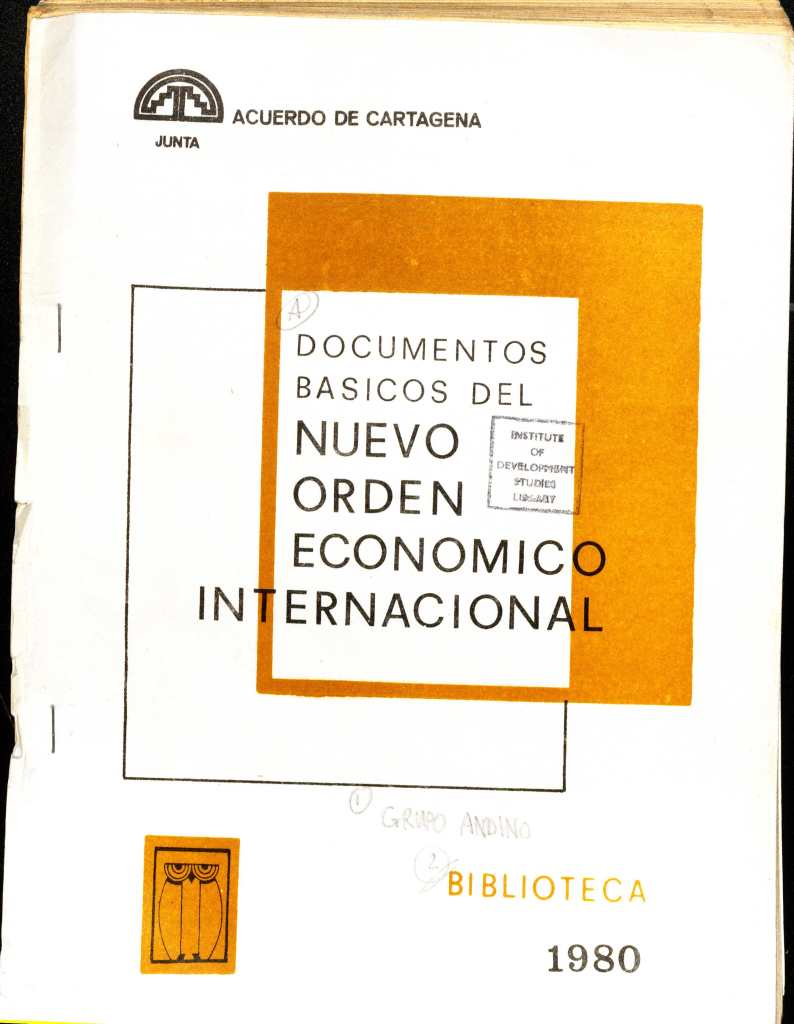

And amazingly the BLDS Legacy Collection also contains documents from the Vienna Conference in our International Organisations section, where we hold the ‘Documentos Basicos del Nuevo Orden Economico Internacional’, which includes (pp. 175-216) the ‘Programa de Accion de Viena sobre Ciencia y Tecnologia para de Desarollo’ including sections on ‘medidas y mecanismos para fortalecer la capacidad cientifica y tecnologica de los paises en desarrollo’ (p. 181 – go on, you can Google Translate this bit).

Vienna was motivated by Group of 77 (the coalition of developing countries founded in 1964 which sought to promote its members’ collective economic interests) aspirations to help factories like CIFEL, though these aspirations were left sadly unrealised as in the 1980s NIEO and NISTO crumbled as these countries struggled with the more immediate struggles of under-development, debt crises and the neo-liberal counter-revolution.

However, we can still see that in 1979 (five years before the original Band Aid single became a well-meaning but damaging symbol of African helplessness and dependence on charity) efforts both on the ground and in the UN showed how it was entirely possible for newly independent countries to develop themselves along their own lines but that this would rely not on charity but on the restructuring of an unfair world system and the acknowledgement of the legacy of colonial exploitation. And we can possibly learn from Sketchley’s inspirational account that the reason this failed was not due to the inadequacy of the people or the socialist project, but because the measures demanded by the Vienna Declaration were rejected by the Global North in favour of an era of supply-side economics and the further commodification of technology.